However, supply chains remain highly vulnerable to social and environmental issues, due to several factors, chief among them:

The lack of visibility into all tier suppliers.

Complex interpretation of requirements

Internal and external data dependencies

And emerging unforeseen supply chain risks

Regulatory landscape - new obligations entering the arena

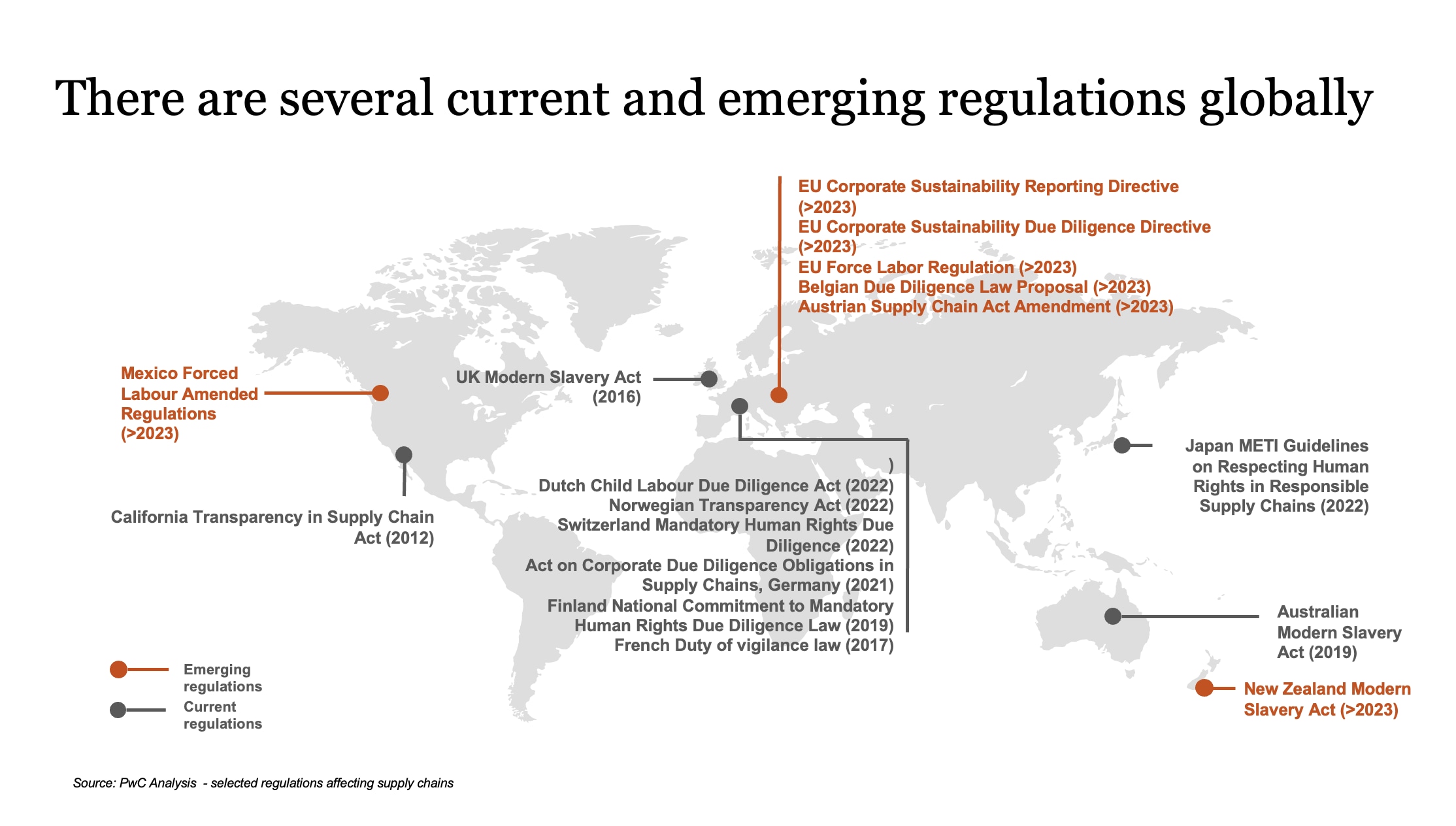

The past months were an opportunity to observe both the EU and selected member states trying to address these key challenges by adopting new due diligence rules limiting environmental and labor risks in corporate supply chains. The United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Norway, and Austria are among the countries that already have modern slavery or human rights due diligence laws in place. Germany, by introducing its Supply Chain Act, also aims to drive corporate sustainability in global value chains, advance the green transition, and protect human rights.

And more is coming with an important milestone that was the 1st of June, which put supply chain management and its challenges firmly front and center. Members of the European Parliament delivered their final position on the EU’s corporate sustainability due diligence directive (CSDDD). The development of this Directive represents a momentous opportunity to ensure that companies conduct meaningful human rights and environmental due diligence throughout their value chains. But the content of the duty matters just as much as its existence. It’s key to align the obligations as closely as possible with the existing, international standards for sustainability due diligence – the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. The new regulation will only apply to certain companies headquartered or operating in the EU, however, their business partners and other companies in their value chains in key sourcing and production markets outside the EU will also be affected.

What key challenges organizations and investors should be aware of?

Supply chains can be highly complex. They often span many countries and include multiple tiers, which are made more opaque by outsourcing and offshoring. They are also essential to the success of almost all businesses and can be a significant source of value creation and innovation. As supply chains fall outside of a company’s core operations, they expose them to hidden and uncontrollable risks typically driven by ESG factors, such as natural resource depletion, human rights abuses and corruption.

These issues can harm the reputations, operations and financial performance of businesses or assets owned by investors, as well as investors’ own reputations and investment performance. Compliance with local regulation is rarely sufficient to meet stakeholder expectations (certain countries in which a supplier may operate may have less robust legal and regulatory standards than others).

While a company may implement the highest ESG performance standards in its own operations, many of its suppliers may not hold similar practices. Studies have estimated that up to 90% of a company’s sustainability impacts originate in a firm’s supply chain. These impacts can hold considerable risk: notably, companies such as Nike, Marks & Spencer, and Hershey’s experienced firsthand the reputational and financial fallout caused by ESG-related issues in their supply chains.

What does a supplier ESG profile include?

Environmental

refers to the resources a supplier uses, the waste it produces, and the resulting consequences of those activities on the planet. This includes water management, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and the use of dangerous chemicals.

Social

refers to how a supplier manages its relationship with internal and external stakeholders. This includes labour relations, employee training and education, reputational issues, and how a supplier fosters positive relationships within the broader community.

Governance

refers to a supplier’s internal framework of procedures, practices, and controls. This includes internal processes utilized to govern itself, comply with regulations, conduct external audits, and guide decision-making.

What key steps can companies take to shore up their supply chains?

Skontaktuj się z nami

Ewelina Łukasik-Morawska