{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

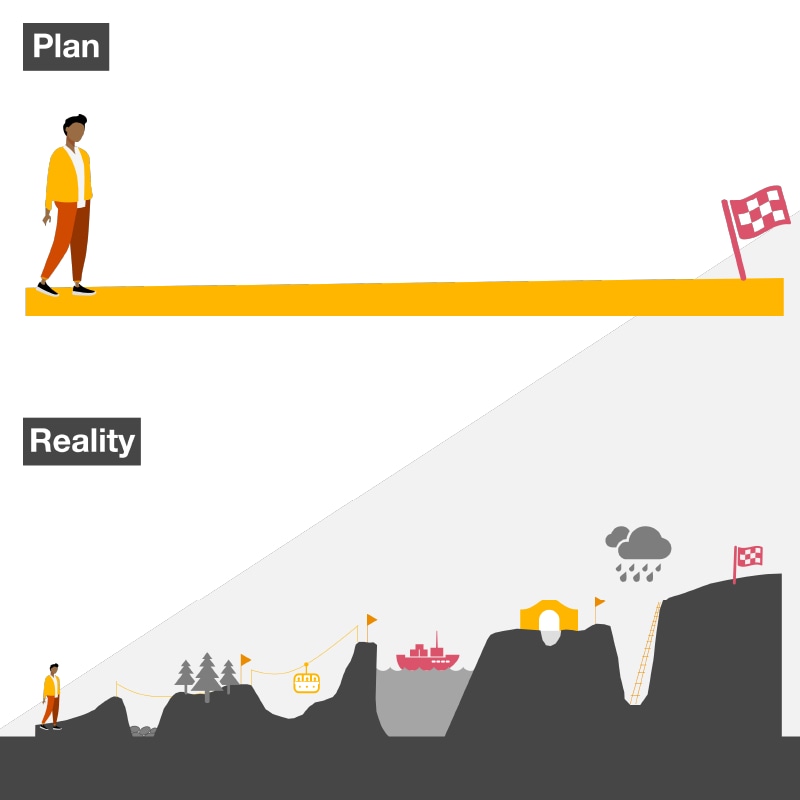

At some point in your life you must have heard about significant projects that were completed months, if not years, behind schedule, despite a huge number of specialists working on them. Possibly they also exceeded the original budget several times. Have you ever wondered why it happens?

In the media we often come across spectacular project planning failures. You may have heard about the Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg scheduled for completion in 2010, with a budget of 77 million euros. Eventually, the concert hall was opened in January 2017 and the budget was exceeded 10 times. Does the problem of inaccurate estimation of budget and completion time affect only large-scale, multi-million projects?

Nothing could be further from the truth! Underestimating the time and money needed for a project happens surprisingly often, even to experienced project managers. Beware of the various pitfalls when you start planning a project!

The planning fallacy is a tendency to incorrectly estimate the time and resources needed to complete a project, partially due to reliance on overly optimistic performance scenarios. It is often linked to traps set by our brains which we are prone to fall into, such as optimism bias, choice-supportive bias, motivated reasoning or anchoring, and adjustment heuristic1.

As the name implies, happens to the Project Manager if she or he is too optimistic about the future implementation of the project. For example, if planning a transfer from the airport to the hotel you do not assume possible delays.

is another trap of the human mind that makes us remember our decisions as the best ones. It does not bypass Project Managers as well. The trap is all the worse for the more experienced people because in new situations they are prone to remembering their own successes and denying their failures.

For example, copying an execution plan from a previous project even though not everything went smoothly.

is the human tendency to consider arguments in favor of conclusions that are closer to us, which we willingly believe, as stronger. As an example, proponents of real estate ownership will look more favorably on the arguments for buying and holding such assets, based on stability, investment potential, and basic security. On the other hand, people who believe that it is better to rent a property will always believe that the purchase and maintenance pose unnecessary restraints and costs for them, and that investments can be made in a different way.

is a trap by which people jump out of their original assumptions and try to adjust other factors, even if it is the assumption itself that is worth changing.

For example, when planning a music festival in March, we might consider how to arrange stage heating or how to minimize the risk of guests tipping over and their possible injuries, instead of changing the original assumption - the month of the project implementation.

How easily we fall into various cognitive traps may depend on our attitude, character traits, personality, or our previous experiences. The remedy is not to fight with our brains, but rather to get to know it and to cooperate with it.

1Roger Buehler, Dale Griffin, Johanna Peetz,“The Planning Fallacy: Cognitive, Motivational, and Social Origins”, in: “Advances in Experimental Social Psychology”, Volume 43, 2010, Pages 1-5.

One of the main factors that may affect the project’s time is ignoring external risks. We tend not to look at a project as part of a large whole that is influenced by many variables. A common mistake in project planning is focusing on specific tasks and forgetting the dependencies between the individual actions and external factors over which we have very little or no control.

The lack of a holistic approach to a project and ignoring all secondary factors can significantly influence the timeframe of the final delivery. Consequently, it may have a negative impact on our profitability2.

Let's take a closer look at a business process transformation case to understand this problem better!

2Jan Kukulies, Bjoern Falk, Robert Schmitt, “A Holistic Approach for Planning and Adapting Quality Inspection, Processes Based on Engineering Change and Knowledge Management”, in: Procedia CIRP Volume 41, 2016, Pages 667-670.

Our project is a business process transition: all business processes should be moved from City A to City B. The cities are almost 2 000 km apart. To make the transition successful, employees of both cities need to travel abroad to train each other.

Two weeks after agreeing on the knowledge transfer schedule, we receive information that the airport workers in City B went on strike, and therefore the air traffic in this country will be temporarily strongly reduced. Online training is only possible to a limited extent, due to the insufficient amount of IT equipment and software currently available in the company. The Project Manager decides to wait for the outcome of negotiations between the airport workers and the authorities, which may normalize the situation.

At the same time, the project team tries to organize alternative transport, which takes extra time and generates extra costs. The project only manages to send abroad 40% of the employees involved (as many flights have been canceled). The remaining 60% do not generate profits for the company as they have been offboarded from other projects with the intention of participating in these transitions.

It turned out that it took almost 8 weeks for airport workers and state authorities to reach an agreement. At one point no person from City A was able to visit City B for a week. The transition process was delayed for a month and the company earned about 15% less than planned due to the additional costs generated by the employees' downtime.

We must remember there is a fine line between ignoring external factors and taking them into account excessively. We have to keep in the back of our minds that we cannot foresee all risks, but the identified ones should be meticulously analyzed in terms of their probability of occurrence, their potential impact on the project and potential response actions.

Another important aspect is the excessive optimism that often accompanies project managers while creating a plan for our project, setting milestones, or estimating deadlines for the deliveries. The tendency to overestimate the probability of positive events occurring in our project while underestimating the probability of negative events is called optimism bias. The main danger is that we may omit an important aspect in our risk analysis because we base the occurrence probability of a risk not on rational premises, but rather on our feelings. Returning to our business process outsourcing case:

Let's assume that those responsible for the transition plan had thought about possible problems in the availability of air traffic, as such situations have occurred in the past. They could have assumed that if such a situation arose again, it would have a major impact on our project.

They could have also envisaged two scenarios from the outset: i.e. to plan the best possible alternative to air transport and to order enough equipment to carry out an online transition if necessary. Their over-optimism however made them conclude that this time it would not happen, as everything so far was going perfectly. As it turned out, the airport employees’ strike reduced the mobility of people from both sites, which consequently had a significant impact on the final success of the whole project.

Are you interested in topics related to project management? Subscribe to our newsletter and stay up to date with the latest knowledge in this area.

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

Marysia Lachowicz